Place your votes: BNA Council & Committee elections

22nd July 2024

20th Jan 2021

A recent article in the British Neuroscience Association (BNA) journal, Brain and Neuroscience Advances, looked at how early-life stress has long-term negative consequences on both mental and physical health.

Individuals who experience childhood maltreatment, including neglect, are more likely to develop psychiatric disorders such as mood and anxiety disorders, and when these do develop, they are more severe than in the general population. Such patients also have higher rates of cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological, and musculoskeletal disease.

Recently, it has been observed that when blood is collected from these patients, the level of inflammation-promoting signaling molecules is often elevated compared to patients with no history of early-life stress.

Together with the fact that immune system activation, or inflammation, is associated with many of the diseases listed above, this raises the question: could the higher rates of mental and physical illness in patients with a history of early-life stress result from the tendency to greater inflammation?

Research using animal models is well-suited to addressing this type of question, because components of the immune system can be targeted with drugs, both during and after early-life stress, to see if detrimental health consequences can be prevented. The most used rodent model of early-life stress is repeated maternal separation (RMS).

This newly published systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of the effects of RMS on key aspects of the immune system. It demonstrates that early-life stress in rodents, as in humans, can lead to higher inflammation in adulthood – but that this may only be the case when individuals are subjected to ongoing stress in adulthood.

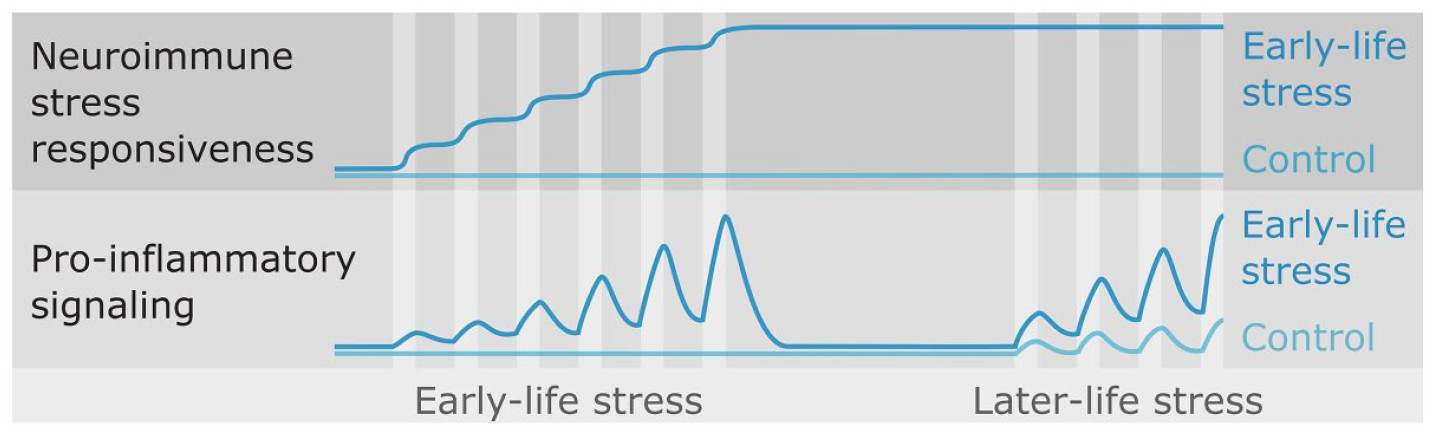

The figure below shows the hypothesised effects of early-life stress (ELS). The findings of this review suggest that ELS exerts a long-lasting augmentation to individuals’ physiological responsiveness to stressors.

The findings suggest that early-life stress causes increased neuroimmune responsiveness to stress, rather than persistently increased inflammation.

As a systematic review (SR), these findings importantly search, appraise and collate all relevant empirical evidence in order to provide a complete interpretation of research results. The findings are critical to furthering an understanding of our response to stress and its part in long-term mental and physical health disorders and helping guide the future use of RMS in understanding the roles of ELS and inflammation in disorders such as depression and cardiovascular disease.

Click here to read the full article

About Brain and Neuroscience Advances

Brain and Neuroscience Advances is a peer-reviewed, open-access journal, which publishes high quality translational and clinical articles from all neuroscience disciplines; including molecular, cellular, systems, behavioural and cognitive investigations.

The journal welcomes submissions in basic, translational and/or clinical neuroscience. Research papers should present novel, empirical results that are expected to be of interest to a broad spectrum of neuroscientists working in the laboratory, field or clinic.

Brain and Neuroscience Advances is now indexed in PubMed Central.

Never miss the latest BNA news and opportunities: sign up for our newsletter